For years, researchers have been looking for ways to harness the medical benefits of psychedelics, but without the hallucinations. Some neuroscientists even believe that the drugs’ mental-health benefits don’t come from tripping at all. Now, for the first time, researchers have developed psychedelic-inspired drugs that bring on neuroplastic effects without producing a trip – a new breed of neuroplastogens.

Neuroplasticity explained

Neural plasticity describes the brain’s ability to change, adapt, and form new connections in response to various stimuli. It’s a vital aspect of healthy brain function, and as such, essential to the way we humans function in our day-to-day lives. Situations in which the brain demonstrates neuroplasticity include learning a new skill such a subject in school or a new language, practicing music, memorizing directions in a new city, and working on puzzles and memory games. It can also occur when a person loses a sense, such as hearing or sight, and their other senses begin overcompensating for the lost one.

Many neurological and psychiatric ailments stem from a lack of neuroplasticity in the brain, which leads to poorly adaptive behavioral responses. Anxiety, depression, and substance abuse are common in people whose brains are unable to strengthen these beneficial circuits. Developing and maintaining neuroplasticity is crucial in promoting recovery from these brain and mood disorders that a large percentage of the adult population struggle with.

Juvenile brains exhibit remarkable neuroplasticity, with both the ability to learn new things as well as the brain being able to quickly mend damaged circuits. But as we grow older, our brains become less plastic and we’re more prone to getting stuck in negative thought and behavioral patterns. This is why external intervention, often in the form of hallucinogenic drugs, is sometimes necessary to repair those broken connections and pathways.

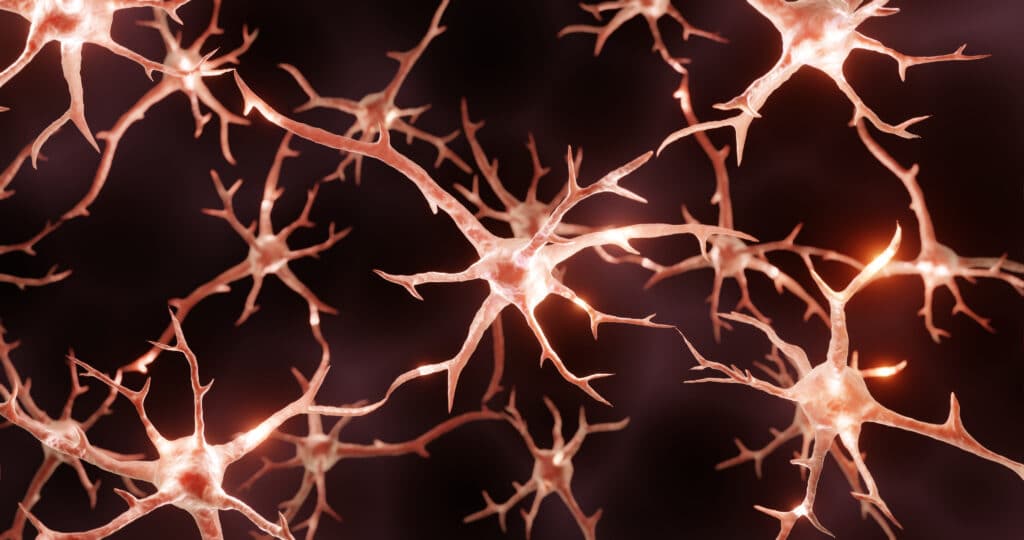

The science of neuroplastogens

Neuroplastogens, also known as psychoplastogens, are a group of small-molecule drugs that are capable of producing rapid and long-lasting effects on both neural structure and function. Many are so potent that they are known to produce the desired therapeutic effects after only a single session. Because of this, neuroplastogens are quickly becoming the go-to option for treating these neurological disorders.

Typically, hallucinogenic drugs like psilocybin and LSD, or dissociatives like ketamine and MDMA, are the gold-standard when it comes to improving neuroplasticity. Recently approved second-generation psychedelics like Spravato and COMP360 work via the same mechanisms. And as incredible as these substances may be, the problem is that not all patients have the time or desire for a psychedelic trip.

A huge number of prospective consumers would prefer to reap the therapeutic benefits of these drugs, without the high. Not to mention, for reasons of liability, when doctors prescribe hallucinogens, the patient needs to be strictly monitored for the duration of their trip, which adds another layer of complexity (as well as higher costs) to the treatment process involving these drugs.

That being said, there is a growing demand for neuroplastogens that are capable of promoting circuit-based plasticity in specific locations of the brain, without unwanted side effects (hallucinations). To meet this unfulfilled need, researchers are exploring the different ways that psychedelics can rewire key areas of the brain, should the psychedelic properties be excluded.

For example, several studies show that ketamine can improve overall mood in humans, even if it’s administered when patients are unconscious. This means that patients who missed out on feeling ketamine’s dissociative effects, because they were not awake for them, still felt happier and less anxious after their operations – which suggests that you don’t need to consciously experience the high in order to benefit medicinally from the drugs.

How do they work?

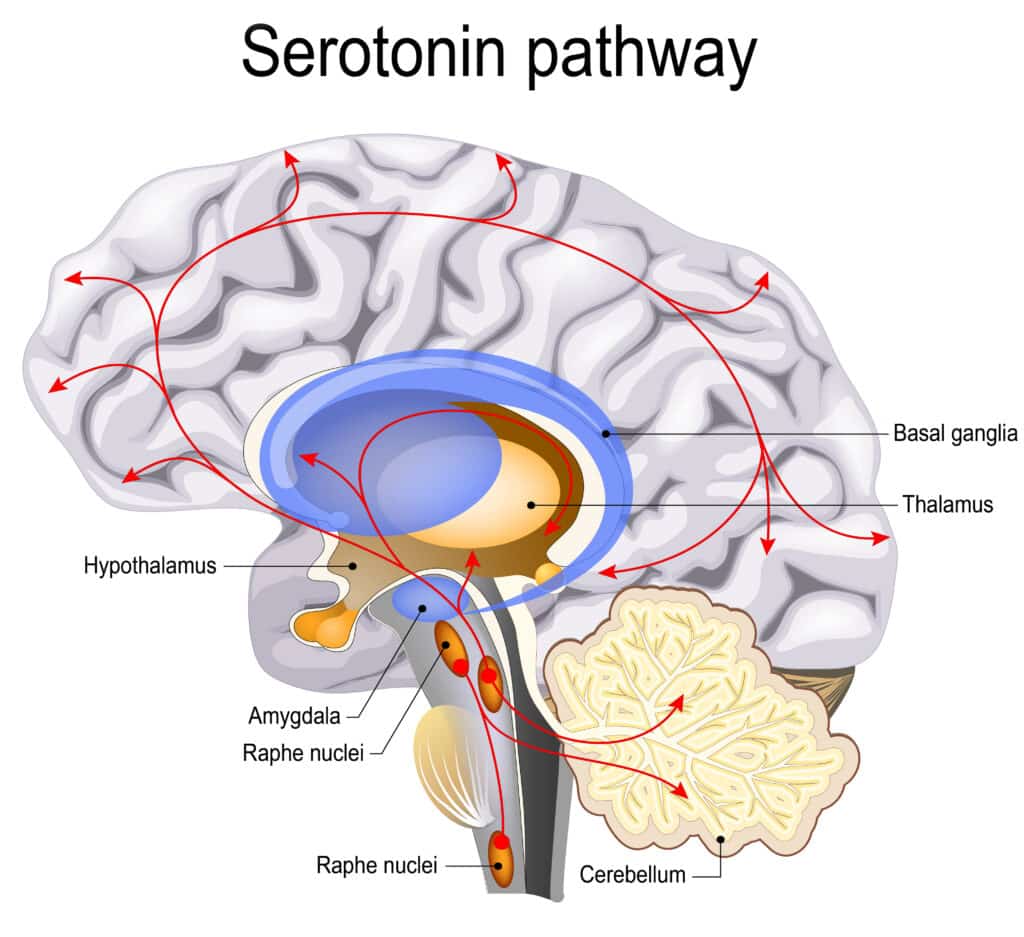

Just like standard psychedelic drugs, these non-hallucinogenic neuroplastogens stimulate the same serotonin receptors, mainly 5-HT2A. When activated, the brain then produces a compound known as brain-derived neurotropic factor (BDNF), which functions as a sort of “brain fertilizer”, that promotes neural growth and survival. While activation of 5-HT2A is often associated with sensory hallucinations, this is not always the case. Different drugs bind to and activate receptors in a variety of ways, which results in very different effects. The focus of non-hallucinogenic psychoplastogens is to activate 5-HT2A serotonin receptors in a way that does not induce a trip.

Some of these trip-free psychedelics are relatively new, like one that was synthesized two years ago (study published in January 2022) by a team of Chinese researchers. The drug works by imitating the mechanisms of lisuride, an analog of LSD, as well as psilocin, the compound that our bodies convert psilocybin from mushrooms into. The drug does not have a name yet, just a serial number, IHCH-7113, and it’s currently undergoing animal trials.

Per the study: “Here, we present structures of 5-HT2AR complexed with the psychedelic drugs psilocin (the active metabolite of psilocybin) and d-lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), as well as the endogenous neurotransmitter serotonin and the nonhallucinogenic psychedelic analog lisuride. Serotonin and psilocin display a second binding mode in addition to the canonical mode, which enabled the design of the psychedelic IHCH-7113 (a substructure of antipsychotic lumateperone) and several 5-HT2AR β-arrestin–biased agonists that displayed antidepressant-like activity in mice but without hallucinogenic effects.”

Other non-hallucinogenic neuroplastogens, although not widely used, have existed for decades. For example, a compound known as 2-Br-LSD (an analog of LSD), was first synthesized in 1957 by Albert Hofmann, the Swiss chemist who created LSD. Renewed interest in this compound has led to new studies, which found that 2-Br-LSD can effectively relieve anxious and depressive behavior in mice, but without twitching and other actions that are common when hallucinations occur. Now, several decades after its initial discovery, a Canadian company, Betterlife Pharma, is planning on conducting the first in-human trials using this trip-free psychedelic.

Are hallucinations just the side-effect? Or something more?

For those of us who truly believe in the healing power of psychedelics, hearing people who have likely never used them talk about how much better these drugs would be without hallucinations… well, it can be disheartening, to say the least. Many of those who have participated in a psychedelic trip describe it as one of the most meaningful and educational experiences of their lives. Not to mention, several studies on psilocybin concluded that the intensity of the trip had a direct correlation on the magnitude and longevity of the therapeutic effects.

Now let’s circle back to those studies about ketamine. Despite people feeling happier after ketamine administration even when they didn’t trip out, there are some questions there that remain unanswered. Comparatively, would the antidepressant effects have been stronger had they felt the hallucinations? How long did the positive effects last after their surgeries, in contrast to patients who experience the drugs in their full scope?

And what about microdosing? Those who take subtherapeutic doses of psychedelic drugs claim to experience many of the neurological benefits – better mood, enhanced creativity, improved focus, and so on – even though the doses they are taking are so low they don’t feel a “high” or experience any sensory hallucinations. However, there are few studies to back up these sentiments, and some people don’t do well with small doses. I personally get very anxious and uneasy when I take low doses of psilocybin, compared to happy, positive highs when I use larger doses.

So, while technically, yes, the hallucinations are a side effect, anyone who has used psychedelics in a serious and intentional way can attest to the fact that visuals and other sensory feelings are informative and powerfully eye-opening. Are they everything these products have to offer? No. Can people benefit from using these drugs without tripping? Absolutely. But are they missing out on a very important piece of the puzzle? Probably so.

Final thoughts

Like most aspects of this industry, more studies need to be done in order to determine how much we are really missing when we remove the trip from psychedelics. Non-hallucinogenic neuroplastogens certainly have an important place in wellness and pharma, as they will expose an entirely new population of mental health patients to the benefits of psychoplastogenic drugs. But which will reign superior? New age neuroplastogens with no hallucinogenic side effects? Or classic entheogens that help transport your senses and your entire being to transcendent new heights? Only time and more research will tell.

Hello readers. We’re happy to have you with us at Cannadelics.com; a news source here to bring you the best in independent reporting for the growing cannabis and hallucinogen fields. Join us frequently to stay on top of everything, and subscribe to our Cannadelics Weekly Newsletter, for updates straight to your email. Check out some awesome promos for cannabis buds, smoking devices and equipment like vapes, edibles, cannabinoid compounds, amanita mushroom products, and a whole bunch more. Let’s all get stoned together!