The urge to improve the world around us is very much a human trait. This really is the entire basis of forming civilizations. It’s the reason we create cities, develop medications, manufacture homes, vehicles, and computers, and it’s why we continue trying to make progressive changes with every incoming generation. This notion of constant improvement is being applied to drugs as well, with some relatively standard objectives as far as modifying hallucinogenic compounds. These include trying to get rid of unpleasant side effects, altering the length and severity of the trip, and sometimes, even removing the hallucinogenic effects entirely (psychedelics that are not psychedelic?).

And this all brings us back to the age-old debate: natural vs synthetic, traditional vs modern, Eastern vs Western, purist vs futurist. In the last few years, we have definitely seen an increase in the recreational use of psychedelics, especially natural ones. But when we look at availability, what compounds are being researched, and what’s gaining FDA approval – it’s synthetics.

The psychedelics industry is on fire, but it might be taking on a different form. In the future, will the psychedelic industry be oversaturated with a bunch of different, synthetic compounds we have never heard of? Will the classics be all but phased out of the legal or medical markets? It’s hard to say for sure, but if you want to stay on top of all the latest, cannabis and psychedelics-related news, make sure to subscribe to The Cannadelics Weekly Newsletter, your top source for all things relating to these blossoming industries.

Natural vs synthetic

Hallucinogenic compounds can be either natural or synthetic. The natural ones are mainly found in plants, such psilocybin from mushrooms, mescaline from peyote, and ibogaine from iboga; while a few select others are produced by animals, like 5-MeO-DMT from the Sonoran Desert Toad. Synthetic hallucinogens are derived from phenethylamine, while natural hallucinogens are typically of the tryptamine class, although there is some overlap. For example, mescaline is substituted phenethylamine. Despite many differences, the molecular structures of all phenethylamines have a couple things in common – contain a phenyl ring, joined to an amino group via an ethyl side chain.

Natural psychedelics have a much richer history than synthetics, having been used ceremoniously by numerous different cultures for centuries. In modern, western culture, psychedelic use has been severely hindered due to overregulation, but for the last few years we’ve been seeing a greater understanding and growing acceptance of these compounds. However, it seems most people are more inclined to favor natural psychedelics, rather than synthetics. This actually doesn’t apply to only hallucinogens, but everything really. Overall, there is this perception that “natural” is healthier, safer, and inherently superior to “unnatural”… and generally, we have found this to be true.

But when it comes to getting patents for medications, and getting them approved by the FDA, it’s many times easier and more likely to happen if the drug is made with synthetic compounds. Just look at the few cannabinoid-based medications we have on the market, such as Marinol and Cesamet. Because these compounds do exist in nature, most consumers think they’re using all natural products, but when it comes to pharmaceuticals, most of what’s available are synthetic alternatives. Only one prescription drug using natural, plant-extracted CBD has received FDA-approval, and that’s Epidiolex, a drug that is being used for the treatment of a couple different rare forms of epilepsy.

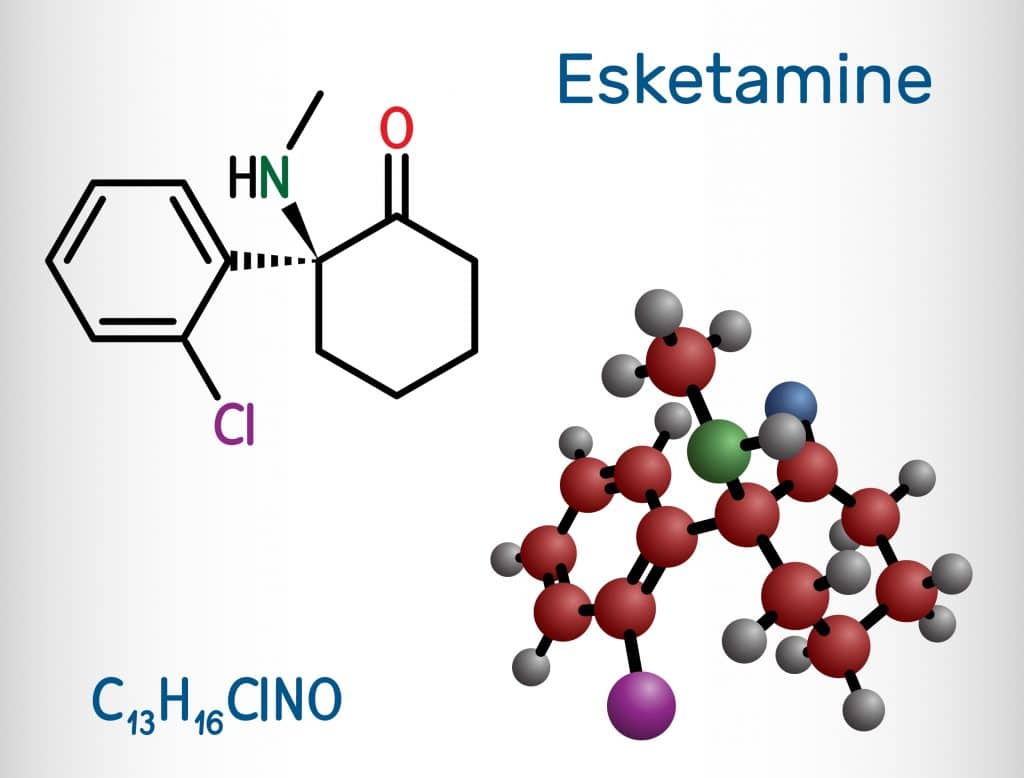

The same concept can be applied to psychedelics. Even though people are generally more comfortable with natural compounds, synthetics are still dominating the research and development sectors. Sure, we’re starting to see more talk about psilocybin, but the majority of psychedelic studies and available treatments thus far have been limited to ketamine and MDMA. Esketamine, which is an enantiomer of Ketamine, received FDA approval three years ago and is prescribed under the brand names Spravato and Ketanest, among others.

Even LSD has a rather extensive history of therapeutic use. Back in 1943, Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann first synthesized lysergic acid diethylamide, and over the next 15 years, over 1000 studies were published on its uses and benefits. During the 1950s and well into the 1960s, LSD was used quite successfully to treat alcoholism, depression, and a handful of other mental health disorders by abridging what could possibly be years of therapy into one or two intensive and self-reflective sessions.

That’s not to say that natural entheogens aren’t gaining popularity as effective therapeutic tools, because they absolutely are. But currently, it’s more common for substances like psilocybin, DMT, mescaline, and so on, to be done in more wellness-type, retreat-like settings, whereas synthetics are what you’re more likely to find in clinics and pharmacies.

Synthetic versions of natural compounds, and improving one existing synthetics

When it comes to replicating natural compounds, the goal is usually to improve them in some way. Think psilocybin without the nausea, or ibogaine without increased heart rate. Many such ideas are circulating at the moment, and some are already in development. A Canadian-based company called Mindset Pharma is working on psilocybin analogues that are five to ten times more potent than natural psilocybin, producing a high that only lasts a couple of hours. They’re also working on another group of compounds that would produce the opposite effects, a trip with barely any hallucinogenic effects.

But researchers aren’t just making synthetic versions of natural compounds, they’re also making new and improved versions of existing synthetics. Like the company Tactogen, who is in the process of developing a “gentler” MDMA-like compound with less stimulant properties, less risk of increased heart rate and blood pressure, and no tolerance build-up; making it much safer for people with cardiovascular conditions. It would still induce the neuroplasticity that MDMA is known for, but without any of the dangerous side effects that street ecstasy is commonly associated with.

Others are looking in a completely different direction, attempting to change the mechanisms by which some drugs work in our bodies. For example, Ron Aung-Din, the clinical medical advisor of Pyscheceutical, discussed a different delivery approach for psychedelics that “avoided the bloodstream all together, through application from a cream or a patch at the back of the neck around the hairline where there are free nerve endings in the skin under the surface, which go right to the brain.” Exciting novel ideas for how to get the psychedelic compounds in our bodies and brains.

Non-psychedelic, psychedelics?

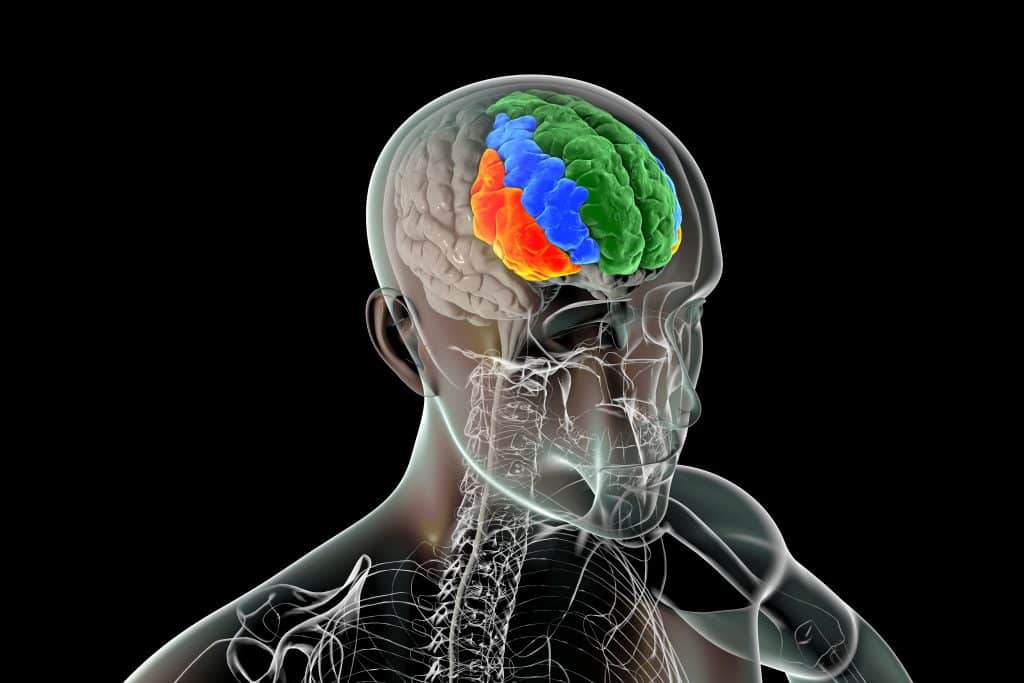

One of the more interesting ideas that researchers have been toying with, is trying to completely remove the psychoactive effects of some of these drugs. For the psychonauts among us, that may seem, for lack of a better word, completely pointless. Afterall, it is believed that the trip is what leads to all the groundbreaking, therapeutic revelations in the first place. And on a certain level, this is true. But, possibly even more importantly, psychedelics also promote neuroplasticity in the prefrontal cortex of the brain, whether one experiences hallucinations or not.

These non-hallucinogenic compounds are being referred to as “psychoplastogens”. Chemical neuroscientist at the University of California Davis and chief innovation officer at Delix Therapeutics, David Olden, along with his colleagues, have developed a library of nearly 1,000 psychoplastogenic compounds, some of which will begin to undergo testing early next year.

There are numerous different uses and indications for non-psychedelic, psychedelic compounds that can be used clinically for a myriad of different health conditions, without inducing a hallucinogenic state. People with psychotic disorders, for instance, are currently prohibited from using psychedelic therapies, for fear the hallucinations could lead to a worsened state of psychosis. But a compound that does not cause hallucinations could be a safer way to treat their conditions. Additionally, this could be used for people who suffer from chronic pain, cluster headaches, and other ailments in which the patient wants to reap the benefits of psychedelics without necessarily experiencing a “trip”.

Another company, Mindstate Design Labs, is looking at this same concept but from a fresh point of view, by creating compounds that produce consistently good trips, or as they put it, “reliably produce the state of oceanic boundlessness or ego loss”.

“[Current psychedelic] compounds are just what happened to be available,” said Dillan DiNardo, Mindstate’s CEO. “And the experiences associated with those compounds are just what happened to be available. By no means is it the full scope of the altered states of consciousness that are possible. New compounds, theoretically, could produce experiences that people have never had before. That’s a challenge in terms of describing them, and even determining if you’ve discovered something new. We will have to develop the validated rating scales to be able to capture the nature of the experience, and the intensity,” DiNardo said.

“A bogus pipedream”

Although undeniably ambitious, drug discovery and development is difficult work. Not only are there many challenging aspects when it comes to simply creating the drugs, but once developed, there is no guarantee that just because its molecular structure is similar to another, that the effects in the human body will be also similar or even predictable. For example, a drug called Ondansetron that is used to treat nausea, interacts with serotonin receptors 5-HT3, but it is in no way a psychedelic drug.

Plus, if it was so easy to tweak and alter drugs to eliminate unwanted side effects, why is this not being applied to more pharmaceutical compounds? Because of this, many critics don’t think the idea of such highly personalized psychedelics is plausible, like Rick Doblin, founder of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), who believes that non-psychedelic psychedelics are a “bogus pipedream”.

Another major facet that seems to be getting overlooked is the patient/user experience. This tunnel vision-like focus on individual drugs and the discovery of new ones can distract from something very important: what should clinicians do with these people when they’re on psychedelics? What are the best methods for treating these patients? And how do different patients, taking different compounds, react to different protocols in therapeutic settings? This will involve much more in-depth research on specific interactions over an extended period of time.

And not to mention, we still don’t even have an extensive amount of data on existing psychedelic compounds, like comparing LSD versus psilocybin in a clinical setting. Does it really make sense to work on creating hundreds of new psychedelic compounds when we’re still just about totally clueless on the full potential of existing ones?

Regardless, the researchers working on these discoveries say their work is vital to the development of the psychedelics industry. “There are components of the current psychedelic compounds that are very important,” Olson said, and shouldn’t be ignored. “But psychedelic science will never realize its true promise if that’s where we stop, if we don’t innovate beyond that,” he said.

“Hundreds, if not thousands of experiments are happening in companies and in research institutions,” said Suran Goonatilake, a co-founder of April 19 Discovery Inc. and a visiting professor at University College London’s Center for Artificial Intelligence. “It’s almost like we now have this permission to innovate around whole classes of receptors that we ignored.”

Patents and FDA approvals

Aside from what seems like complete customization, another benefit to creating new compounds is access and scalability, meaning it is much easier to get patents for synthetics. It makes sense, since patents are granted for “new” inventions, how can anyone patent nature? The only way to own a compound like this is by creating a very similar but noticeably varied version, and then getting a patent for it. Companies like Atai Life Sciences are already claiming that they will “focus on the generation of intellectual property” from this point forward.

And patented compounds are also more likely to get FDA approval. When we consider what has already been legalized for pharmaceutical use – like Marinol which is a synthetic version of THC, or even Esketamine, which is not replacing any natural compound, but is an optical isomer of ketamine – we start to see a pattern.

They want us using their drugs exclusively. And why wouldn’t they? The pharmaceutical industry is one of the most profitable in the United States, and they’re showering congress members with cash in the form of political lobbying and various campaign distributions. Every year, the federal government receives millions of dollars from pharmaceutical companies, and for obvious reasons, they want this relationship to continue.

Patents can also help secure funding to research and develop even more drugs. So, this brings up some interesting questions and ideas, like whether the benefits of these drugs will be overstated in marketing campaigns now that money is on the line. Will this lead to the development of compounds with very little improvements simply because this new compound can be owned and turned for a profit?

Matt Baggott, a neuroscientist and the co-founder and CEO of Tactogen, says that, from scientific and economical standpoints, it’s unlikely and doesn’t make sense for an infinite amount of new compounds to be created. “I do think that we’re going to hit a point where it’s not going to make financial sense for companies to continue to develop products.” He added that “a lot of the patent applications you hear about or read about, I think, are really designed to secure the company’s kind of ability to operate.”

Final thoughts

Are “precision psychedelics” the way of the future? A few years from now, will we be faced with a psychedelics market that’s almost entirely synthetic, full of recently developed compounds we know little to nothing about? While the idea of a personalized drug experience certainly sounds interesting, it does seem a bit obtuse to focus on the creation of new compounds rather than gaining more knowledge about the ones we already have. But if the whole point is to make money off patentable products, then it’s possible that the psychedelics industry will one day see the level of variation that we’re currently experiencing in the cannabis industry, with the recent introduction of dozens of new cannabinoids, many of which are synthetic.

So, how many psychedelic-like drugs will exist in the future? That part remains unclear. It will depend on where consumer demand sits for these products, which ones have the highest profit margin, and hopefully also of consideration, which of these drugs actually work.

Hello and welcome! You’ve made it to CBDtesters.co/Cannadelics.com, the #1 web spot for the most comprehensive independent news coverage of the cannabis and psychedelics industries. Join us whenever possible to stay in-the-loop on the ever-changing landscape of cannabis and psychedelics, and subscribe to The THC Weekly Newsletter, so you’re always on top of what’s going on.