While some countries remain uptight with drug policy, others are so loose, they’re practically coming apart at the seams. Now British Columbia follows in the footsteps started by Portugal in 2001, with an announcement that the Canadian Province is set to decriminalize hard drugs.

British Columbia and the announcement to decriminalize hard drugs does not paint a very good picture of what’s going on with overdoses these days. Is decriminalizing drug possession really helpful in this situation, though? We’re an independent news site specializing in cannabis and psychedelics reporting. Follow along by subscribing to The Cannadelics Weekly Newsletter, and also get yourself in first place for future product promotions.

What’s going on?

Canada was the second country after Uruguay to pass a nationwide recreational cannabis legalization back in 2018. And now, one of its provinces is stepping it up even more. On May 31st, 2022, the federal government of Canada announced that the province of British Columbia would decriminalize hard drugs in the upcoming year. By January 31st, 2023, adults (18+) in the province will be able to possess small amounts of hard drugs in the amount of 2.5 grams or less. This applies to opioids, cocaine, methamphetamine, and MDMA.

How did this come about? It’s not a part of general Canadian policy to allow hard drug possession. In November 2021, British Columbia applied for a federal exemption from the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. It requested a 4.5 gram threshold, which the federal government reduced to 2.5 grams upon approval.

This threshold might be debatable in the future according to federal minister of mental health and addictions, Carolyn Bennett, who called the current limit a ‘starting point’, that could be adjusted as per need. Bennett explained that 85% of seizures are for under two grams.

This comes from the British Columbia Association of Chiefs of Police, which says the average amount taken in seizures of hard drugs varies from about 1.3 grams to 1.9 grams, depending on location. However, if you ask those who use the drugs, their story is that 2.5 grams isn’t enough to cover the reality of what hard drug users must use daily to maintain themselves.

This entire measure is seen as a harm reduction measure due to the massive drug issues in the province. British Columbia isn’t set to decriminalize hard drugs just to do it. It’s trying to placate its growing number of addicted drug users, who must continue taking their drugs to feed their addictions. Many of whom are on opioids, which were legally provided to them.

Issues with this

The whole fact this is happening indicates a massive issue to begin with. Could the government’s acquiescence to such a measure indicate a level of guilt? Governments don’t usually substantiate the drug use of their people, yet that’s exactly what’s happening. And its not comparable to Portugal, which was dealing with illegal drug problems, and which saw improvement by decriminalizing. This issue is based on the idea that doctors are now the primary drug dealers. This current and rising opioid epidemic is a government-sanctioned drug epidemic, so it cannot be gotten rid of so long as doctors are writing prescriptions, and this isn’t stopping.

There are many worrying factors about this decriminalization. As per Ryan McNeil, director of harm-reduction research at the Yale Program in Addiction Medicine, who is also an affiliated scientist at the B.C. Centre on Substance Use:

“Two-point-five grams is difficult to eyeball — how are police necessarily going to be equipped to eyeball that in the field? Does that mean this might become a mechanism by which anything above that threshold becomes understood to be potentially possession with the intent to sell, or marks someone as potentially selling drugs. We need to raise questions about how this will actually be implemented in real world settings and whether it might perpetuate the inequities that we see in the policing and potential incarceration of especially Indigenous people but also other folks who are racialized.”

Many of those currently reliant on hard drugs argue that the limit itself is problematic in that many users require more than this. Vice-president of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users, Kevin Yake, who uses hard drugs himself, said the policy sets users up to fail. He put it this way:

“At 4.5 grams, I thought that was low. Two-point-five grams, I think that’s ridiculous. I need that to wake up in the morning. For people with higher tolerances it doesn’t really cut it at all.” He explained that this might impact how people buy, forcing them to buy in smaller amounts, which means increased transactions, more money spent, and more risk. “Now it’s a new ball game — make sure I have enough for that day because I’ve got to score again.”

British Columbia and drug overdoses

The opioid epidemic is often referenced in America, but the reality is that many countries have growing issues with drug overdoses, particularly from synthetic opioids. And British Columbia is not exempt. In fact, British Columbia has so many deaths, that this is why its set to decriminalize hard drugs, in an effort to help those who are strung out. British Columbia is the third most populous province in Canada with about 5.2 million inhabitants.

In 2016, the province declared a public health emergency due to drug overdoses. Since that time, more than 9,400 people in the province died from overdosing, which makes for an average of six people a day. In 2021 alone, 2,224 or more fatal overdoses happened in the region. The rate of death from illicit drugs went up 400% in the past seven years. 2021 numbers are 26% higher than the previous year.

It should come as no surprise that in 2021, 83% of samples from overdoses tested positive for fentanyl, and another 187 results showed positive for fentanyl analogue carfentanil, which is close to triple the number of positive samples for that compound found in 2016. In 2021, 71% of suspected overdose victims were between 39-59 years old. Vancouver, Surrey, and Victoria were the townships with the highest overdose volumes in the province.

So British Columbia is having a massive drug overdose problem, and at the center of it is synthetic opioids, which are legally produced and sold. This is not a black market drug issue, but the continuation of a pharmaceutical company started problem, which has been promoted by governments allowing the medications through regulation. Now, a huge problem is ballooned out, and the best Canada can think to do with all these people it helped get addicted, is make drugs more socially acceptable to have.

Why isn’t ketamine used?

The saddest part to all this, is that there is an answer. It’s just being ignored by local governments. Sure, it’s a highly complicated issue, with lots of moving pieces. You’ve got the pain issue that got a lot of people addicted in the first place, you’ve got the current addictions which are now formed and must be treated, and you’ve got the issues related to drug cessation for an addicted person. On top of all this, you’ve got the fallout from these addictions in the form of money lost to individuals, as well as the taxpayer money paid out for everything from emergency services to healthcare costs.

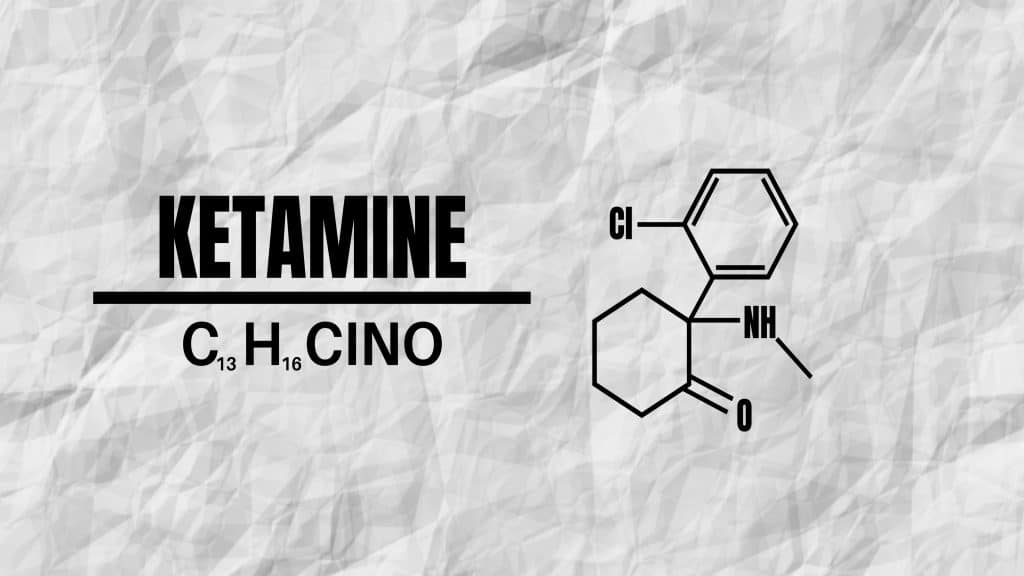

So anything that can help should be used, and should be used immediately. Which is why its baffling that ketamine, a Parke-Davis founded dissociative hallucinogen, is not so much as brought up to help this situation. In America, ketamine is only approved by the FDA for treatment-resistant depression (in the form of esketamine), but its widely used off label in clinics for pain control. In Canada, it’s a Schedule I drug, which means it requires prescription for sale.

It’s been known that ketamine is a good pain control drug since the 1960’s, when it was the subject of prisoner studies. It worked well enough at that time, that it was subsequently used on the fields of Vietnam. Part of the reason it provides a good method, is that it doesn’t lower heart rate or breathing rate, and therefore makes overdosing that much more difficult. Ketamine has no real death toll, and I have yet to find a statistic for ketamine deaths that doesn’t include the use of other drugs. Ketamine’s lack of physical addiction, means users won’t get addicted and can stop when they want.

Just in case there’s a misunderstanding about how ketamine can be used, it’s already been investigated as an opioid alternative. In this review of 76 papers, its found that ketamine is a safe and effective alternative treatment to opioid therapy. Another example is this study, which was done using 870 adult patients, all of whom showed up to emergency rooms with severe pain. The study demonstrates how ketamine performed as a comparable treatment measure to opioids for acute pain control.

One last thing about ketamine, is its shown useful for the circular and compulsive thoughts of addiction, an important aspect when dealing with addicts. This is evidenced in studies on eating disorder patients, where after ketamine treatment, the majority reduced or eliminated their compulsive thoughts. Something that persisted well after the ketamine was given. Ketamine, like other hallucinogens, seems to have the ability to help people leave their normal thought patterns, and create entirely new ones. Though there are certainly some safety issues involved with ketamine use, these issues are generally related to how its given, and are not associated with death.

Conclusion

Canada could be looking into getting its addicted population switched over to ketamine in order to save lives, but instead, is changing laws to make drugs more available and socially acceptable, without mentioning ketamine at all. Why? If you’re a citizen wondering how this problem can actually be solved, and not just temporarily placated, this is a question worth asking.

Welcome all! Thanks for stopping by Cannadelics.com. We’re happy to bring you honest and direct reporting of the growing cannabis and psychedelics industries. Join us frequently for daily updates on everything going on, and subscribe to The Cannadelics Weekly Newsletter, so you’re never late on getting a story.